COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) is a respiratory tract infection with a newly recognized coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2

Illness ranges in severity from asymptomatic or mild to severe; a significant proportion of patients with clinically evident infection develop severe disease, which may be complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome and shock

COVID-19 disease severity (1)

Mild disease: symptomatic patients with suspected, probable, or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection without evidence of viral pneumonia or hypoxia

Moderate disease: requires presence of pneumonia (diagnosis for which typically entails chest imaging)

Adolescent or adult with clinical signs of pneumonia (eg, fever, cough, dyspnea, fast breathing) but no signs of severe pneumonia, including SpO₂ greater than or equal to 90% on room air

Child with clinical signs of non-severe pneumonia (eg, cough or difficulty breathing plus fast breathing and/or chest indrawing) and no signs of severe pneumonia

Severe disease: requires presence of severe pneumonia (diagnosis for which typically entails chest imaging)

Adolescent or adult with clinical signs of pneumonia (eg, fever, cough, dyspnea, fast breathing) plus one of the following: respiratory rate greater than 30 breaths per minute, severe respiratory distress, or SpO₂ less than 90% on room air

Child with clinical signs of pneumonia (cough or difficulty in breathing) plus at least one of the following:

Central cyanosis or SpO₂ less than 90%, severe respiratory distress (eg, fast breathing, grunting, very severe chest indrawing), general danger sign (eg, inability to breastfeed or drink, lethargy or unconsciousness, or convulsions)

Fast breathing (in breaths/min): < 2 months: ≥ 60; 2–11 months: ≥ 50; 1–5 years: ≥ 40

Infection ranges from asymptomatic to severe; symptoms usually include fever, cough, and (in moderate to severe cases) dyspnea. Disease may evolve over the course of a week or more from mild to severe; deterioration may be sudden and catastrophic (2)

Among patients who are symptomatic, the median incubation period is approximately 4 to 5 days, and about 98% have symptoms within 11 days after infection (3)

History

Most common complaints are fever (more than 80%) and cough, which may or may not be productive (4, 2)

Other common symptoms include upper respiratory symptoms (rhinorrhea, sneezing, sore throat), myalgias and fatigue, the latter of which may be profound (2)

Alteration in smell and/or taste is widely reported, often as an early symptom, and is highly suggestive; absence of these symptoms does not exclude the diagnosis (5)

Uncommon manifestations include hemoptysis, pleuritic chest pain, headache, and gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) (6, 2)

Physical examination

For moderate or severe disease, common signs are fever (often exceeding 39°C) and respiratory distress (1)

Patients in the extremes of age or with immunodeficiency may not develop fever

Tachypnea and labored respirations usually indicate moderate to severe disease; if distress is apparent, immediately assess airway, breathing, and circulation (eg, pulses, blood pressure)

Described cutaneous manifestations include: erythematous rashes, purpura, petechiae, and vesicles (7, 8, 9, 10)

Hypotension, tachycardia, and cool/clammy extremities suggest shock (1)

Testing indications

CDC and WHO have slightly different criteria for whom to test but both support testing hospitalized patients with a clinically compatible illness (11, 12)

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Test patients with acute onset of fever and cough or acute onset of any 3 or more of a specified list of symptoms (eg, fever, cough, general weakness/fatigue, headache, myalgia, sore throat, coryza,dyspnea, anorexia/nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, altered mental status) plus one of the following:Living or working in a setting with high risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (eg, closed residential facilities, refugee camps) at any time during the 14 days preceding symptom onsetA history of travel to or residence in an area reporting local transmission of COVID-19 during the 14 days preceding symptom onsetWorking in any health care setting at any time during the 14 days preceding symptom onset

Onset within the last 10 days of a severe acute respiratory tract infection requiring hospital admission without an alternative etiologic diagnosis

In situations where testing must be prioritized, test the following:Patients at high risk for severe disease and hospitalizationSymptomatic health care workersFirst symptomatic persons in closed-space environments (eg, schools, long-term care facilities, hospitals, prisons), representing possible index cases WHO: World Health Organization 1. WHO: Clinical Management of COVID-19: Interim Guidance. WHO website. Updated May 27, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1278777/retrieve 2.

Reasonable to test patients with a clinically compatible illness; however, clinicians should use judgement, informed by knowledge of local COVID-19 activity and other risk factors, to determine the need for diagnostic testing

Maintain a low threshold for testing persons with extensive or close contact with people at high risk for severe disease in their home or employment setting

Testing may also be recommended in other circumstances:Any person (even if asymptomatic) with recent close contact with a person known or suspected to have COVID-19Asymptomatic persons without known or suspected exposure in certain settings (eg, closequarters community, preoperative setting)To document resolution of infection (not routine but may be appropriate in certain circumstances)Public health surveillance CDC: Centers for Disease Control 1. WHO: Clinical Management of COVID-19: Interim Guidance. WHO website. Updated May 27, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1278777/retrieve 2. CDC: COVID-19: Overview of Testing for SARS-

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Primary diagnostic tools

Diagnosis is confirmed by detection of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA on polymerase chain reaction test of upper or lower respiratory tract specimens 11, 13

Alternative methods for diagnosis are antigen tests or (in unusual cases) serology

Antigen testing has equivalent specificity but is slightly less sensitive 14

Antibody (serologic) testing is not recommended for routine diagnostic purposes 15, 16, 17, 11

Chest imaging is essential to document presence of pneumonia and to assess severity; plain radiography, CT, and ultrasonography are used for this purpose 4

Note that chest radiograph and/or CT are not specific diagnostic measures for COVID-19 since findings overlap with other viral pneumonias 18

Repeat testing after initial negative result

Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines provide additional guidance and an algorithm, including indications for repeated testing when suspicion for disease is high but initial test result is negative 20

For patients with high likelihood of disease but negative initial result, repeated testing is recommended; in patients with lower respiratory tract symptoms, sputum or other lower respiratory tract specimen is recommended for repeated testing 20

Adjunct testing is generally unnecessary for cases of mild COVID-19

Laboratory

PCR assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid

Specimen sources for PCR include secretions from nasopharynx, midturbinate, anterior nares, oropharynx, or saliva 14, 21

A systematic review and meta-analysis compared frequency with which SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in sputum, nasopharyngeal swabs, and oropharyngeal swabs in patients with documented COVID-19. Overall positivity was 71% for sputum, 54% for nasopharyngeal swabs, and 43% for oropharyngeal swabs. 22 Sensitivity of PCR testing of nasopharyngeal swabs is high just before and soon after symptom onset 2

Antigen testing to identify SARS-CoV-2

Antigen tests are less sensitive than polymerase chain reaction, although specificity is equivalent and may be as high as 100% 16

False-positive results are uncommon, but a negative result may warrant retesting (preferably within 2 days) with polymerase chain reaction if there is a high suspicion for infection 16

A Cochrane review noted wide-ranging sensitivity and specificity of antigen tests (average sensitivity, 56.2%; average specificity, 99.5%) 23

Serology (antibody testing)

Serology is not recommended for routine use in diagnosis, but it may be useful under some circumstances (eg, high suspicion for disease with persistently negative results on viral RNA tests) 17

Antibody tests are most likely to be clinically useful 15 days or more into the course of infection; data are scarce regarding antibody tests beyond 35 days 24

Other laboratory findings are variable but typically include lymphopenia and elevated lactate dehydrogenase and transaminase levels

Imaging

Chest radiograph

Chest imaging in symptomatic patients almost always shows abnormal findings, usually including bilateral infiltrates, varying from consolidation in more severely ill patients to ground-glass opacities in less severe and recovering pneumonia 27, 28

Chest CT

CT appears to be more sensitive than plain radiographs, but normal appearance on CT does not preclude the possibility of infection with SARS-CoV-2 29, 27

Chest ultrasonography 30,21

Bedside ultrasonography is widely used to monitor progression of pulmonary infiltrates, and to assess cardiac function and fluid status; it may also be used to detect deep vein or vascular catheter thrombosis, which appear to be common in patients with COVID-19

Management of moderate to severe COVID-19 largely involves treating pneumonia Specific treatments and treatment strategies are emerging; overall treatment strategy is based upon stage and severity of disease 23

Treatment broadly consists of isolation precautions, anti-viral drug therapy, corticosteroids/immunomodulators, and supportive care measures

Isolation precautions (in health care facilities) 31, 32

Supply each patient with a face mask and place in an appropriate closed room (negative pressure and frequent air exchange preferred; when hospitals are crowded, reserve negative pressure isolation rooms for the greatest needs (ie, aerosol-generating procedures; tuberculosis, measles, and varicella)

Persons entering the room should follow standard, contact, and droplet or airborne precautions (N-95 mask, gloves, gowns, eye protection)

CDC recommends a symptom-based (rather than a testing-based) strategy to determine when to discontinue isolation in most patients. This means at least 10 days since symptoms onset and 24 hours without fever. If asymptomatic infection, at least 10 days since first positive specimen

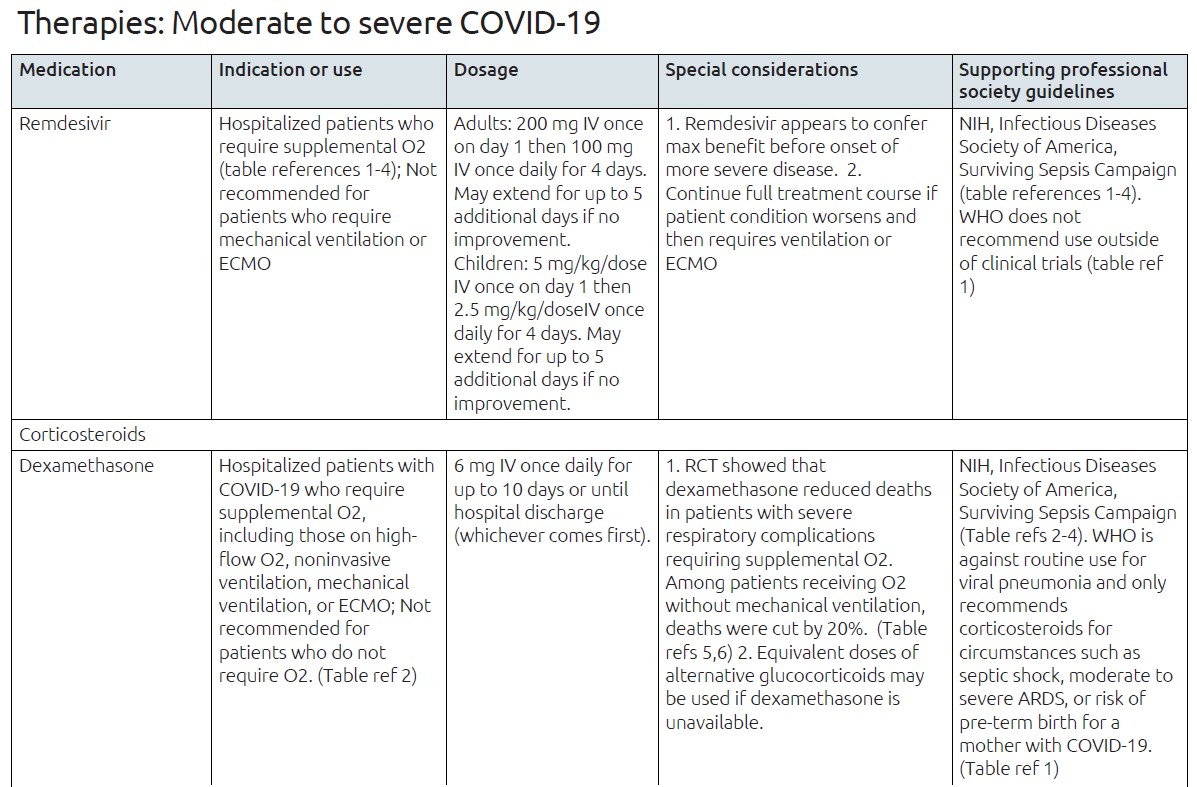

Anti-viral drug therapy

Remdesivir is an anti-viral drug specifically designated for treatment of COVID-19 in adults, children, and infants or neonates 33

Recommended use is for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who require supplemental oxygen; it is NOT appropriate for patients in critical care settings who require invasive mechanical ventilation and/or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation 34, 35, 36, 37

However, for patients whose condition worsens while they are receiving remdesivir and who require ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, the treatment course should be completed 34

Remdesivir (and other antivirals or monoclonal antibodies) is proposed to be most effective when used early in the course of infection to prevent cell entry and viral replication 23

Guidelines do not recommend remdesivir for mild COVID-19 (those who do not require supplemental oxygenation), even if hospitalized 34, 37, 35, 36

Data supporting its use derives from the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial, a placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial of1062 patients which showed a statistically significant improvement in time to recovery and a nonsignificant trend in lower mortality 38, 39

Corticosteroids/ Immunomodulators

Corticosteroid therapy is suggested for patients with COVID-19 who require supplemental oxygen with or without mechanical ventilation (optional for patients who require oxygen supplementation only, that is, without high-flow oxygen, noninvasive ventilation, or invasive mechanical ventilation); professional societies uniformly do NOT recommend using dexamethasone in patients who do not require oxygen supplementation 34, 37

WHO is more conservative, and recommends against routine use of corticosteroids for viral pneumonia, but it notes that some clinical circumstances may warrant use (eg, septic shock, moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, risk of preterm birth associated with COVID-19 in the mother) 1

A randomized controlled trial in more than 6000 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 found that dexamethasone reduced deaths in patients with severe respiratory complications requiring supplemental oxygen 40

In the RECOVERY trial, dexamethasone reduced mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19; the benefit was limited to patients who received supplemental oxygen and was greatest among patients who received mechanical ventilation 40

Dexamethasone did not improve outcomes, and may have caused harm, among patients who did not receive supplemental oxygen, and thus it is not recommended for the treatment of mild COVID-19 40

Alternative glucocorticoids such as methylprednisolone or prednisone may be used if dexamethasone is not available 34

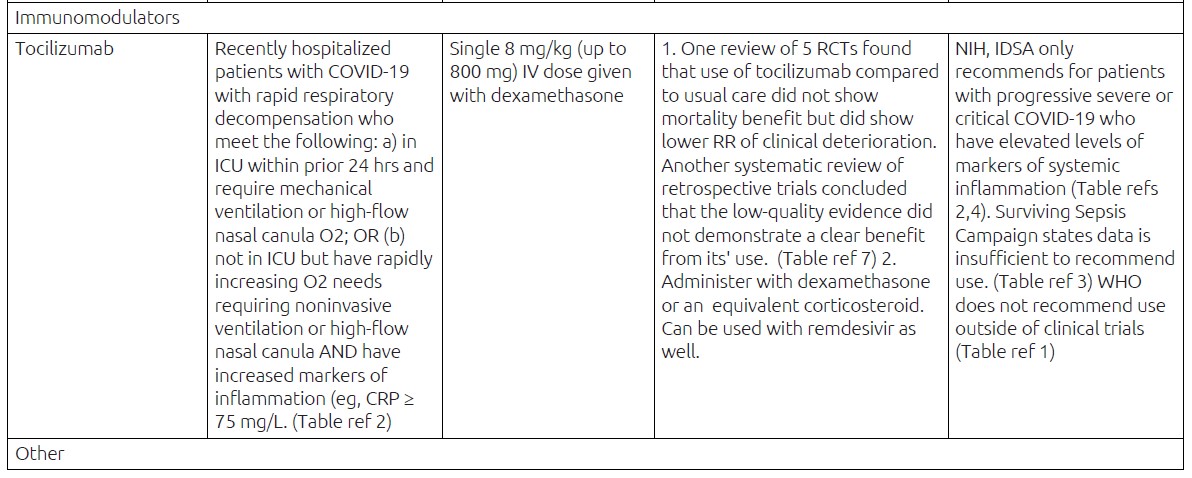

Immunomodulators are also being investigated for mitigation of cytokine release syndrome believed to be a factor in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID-19

Infectious Diseases Society of America suggests against the routine use of tocilizumab, based on evidence of low certainty, but does recommend tocilizumab in combination with corticosteroids for patients with progressive severe COVID-19 who have elevated levels of markers of systemic inflammation ("cytokine storm") 37

Likewise, NIH COVID-19 treatment guideline recommends tocilizumab in combination with dexamethasone (with or without remdesivir) in recently hospitalized patients who are showing rapid respiratory decompensation. 34

Those who require invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen

Those with rapidly increasing oxygen needs requiring noninvasive ventilation or high-flow nasal cannula and who have significantly increased levels of inflammatory markers

Supportive care measures

Supportive measures for patients with moderate to severe COVID include oxygen supplementation and conservative fluid support, along with usual measures to prevent common complications (eg, pressure injury, stress ulceration, secondary infection) 1

Overhydration should be avoided, because it may precipitate or exacerbate acute respiratory distress syndrome

Oxygenation should begin when oxygen saturation falls below 90% to 92% 36, 1

Nasal cannula at 5 L/minute or face mask with reservoir bag at 10 to 15 L/minute

Titrate to reach SpO₂ of 94% or more initially; once stable, target SpO₂ of 90% or higher in nonpregnant adults; 92% or higher in pregnant patients, and 90% or higher in children

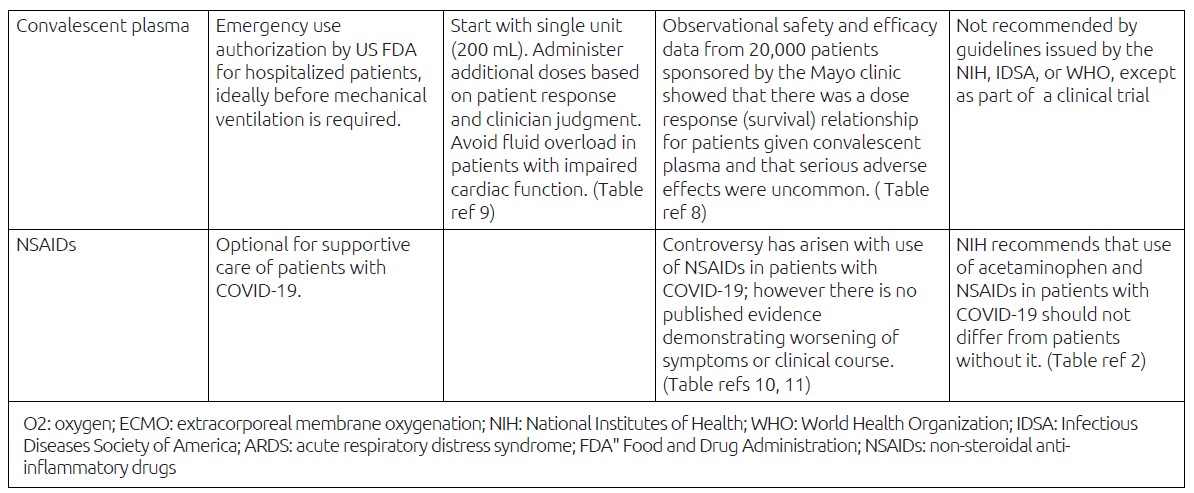

Antipyretics (NSAIDs, acetaminophen) may be used for fever and pain; at present there is no convincing evidence that the disease worsens or severe adverse events occur in patients who use NSAIDs 41, 34

Employ usual prophylactic regimens for thromboembolism for all patients hospitalized with COVID-19, including pregnant patients 42, 43, 44, 45

Consider continued thromboembolism prophylaxis for patients at high risk (as deemed by risk assessment) for up to 45 days after discharge 42, 43, 44

Other supplementary or interim therapy Appropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy for other viral or bacterial pathogens should be administered in accordance with the severity of clinical disease, site of acquisition (hospital or community), epidemiologic risk factors, and local antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, until a diagnosis of COVID-19 is confirmed by laboratory testing 1

Investigational therapies

Use of convalescent plasma is largely delegated to clinical trials 34, 37, 1, 35

FDA recently issued emergency use authorization for high titer COVID-19 convalescent plasma for hospitalized patients citing observational safety and efficacy data from 20,000 patients who received convalescent plasma through a program sponsored by the Mayo Clinic 46

Data suggest that use of COVID-19 convalescent plasma with high antibody titer may be effective in treating hospitalized patients with COVID-19 when administered early in the course of disease or when administered to patients with impaired humoral immunity

Evidence of improved survival was found in the subset of patients treated with convalescent plasma containing higher versus low titers of neutralizing antibody (ie, a dose-response gradient)

Serious adverse events were uncommon, and they were judged not to exceed the known incidence in transfusion of plasma to critically ill patients

1. WHO: Clinical Management of COVID-19: Interim Guidance. WHO website. Updated May 27, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1278777/retrieve

2. NIH: COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. NIH website. Updated April 21, 2021. Accessed April 25, 2021. https://covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/

3. Alhazzani W et al: Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines on the management of adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the ICU: first update. Crit Care Med. ePub, February 2021

4. Bhimraj A et al: Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Treatment and Management of Patients With COVID-19. IDSA website. Updated April 14, 2021. Accessed April 25, 2021. https://www.idsociety.org/COVID19guidelines

5. RECOVERY Collaborative Group et al: Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19- -preliminary report. N Engl J Med. ePub, July 17, 2020

6. Chief Investigators of the RECOVERY trial (Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy): Low-Cost Dexamethasone Reduces Death by up to One Third in Hospitalised Patients With Severe Respiratory Complications of COVID-19. RECOVERY trial website. Updated June 16, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.recoverytrial.net/news/low-cost-dexamethasone-reducesdeath- by-up-to-one-third-in-hospitalised-patients-with-severe-respiratory-complications-of-covid-19

7. Lan SH et al: Tocilizumab for severe COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 106103, 2020

8. FDA: Clinical Memorandum on COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma. FDA website. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/141480/download

9. FDA: Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers: Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma for Treatment of COVID-19 in Hospitalized Patients. FDA website. Published August 23, 2020. Updated February 4, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/141478/download92

10. FDA: FDA Advises Patients on Use of Non- Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) for COVID-19. FDA website. Updated March 19, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-advises-patients-use-non-steroidal-anti-inflammatory-drugs-nsaids-covid-19

11. Rinott E et al: Ibuprofen use and clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. ePub, June 12, 2020

Most common complications in patient with moderate to severe COVID-19 include progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome (60-70%), shock (30%), myocardial injury (20-30%) arrhythmias (44%), acute kidney injury (10-30%) 2, 4, 21

Other reported complications include thrombotic events and secondary bacterial or fungal infections 2, 44, 4

Mortality rate among diagnosed cases (case fatality rate) is generally about 3% globally but varies by country; true overall mortality rate is uncertain, as the total number of cases (including undiagnosed persons with milder illness) is unknown 47, 48

Knowledge of this disease is incomplete and evolving; moreover, several variants with potential impact on transmission, clinical disease, and immune protection have been recognized

1 WHO: Clinical Management of COVID-19: Interim Guidance. WHO website. Updated May 27, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. 2 Huang C et al: Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 395(10223):497-506, 2020 3 Lauer SA et al: The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application. Ann Intern Med. 172(9):577-582, 2020 4 Chen N et al: Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. ePub, January 30, 2020 5 Spinato G et al: Alterations in smell or taste in mildly symptomatic outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. ePub, April 22, 2020 6 Chan JFW et al: A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 395(10223):514-23, 2020 7 Recalcati S: Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. ePub, March 26, 2020 8 Joob B et al: COVID-19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for dengue. J Am Acad Dermatol. 82(5):e177, 2020 9 Marzano AV et al: Varicella-like exanthem as a specific COVID-19-associated skin manifestation: multicenter case series of 22 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. ePub, April 16, 2020 10 Magro C et al: Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. ePub, April 15, 2020 11 CDC: COVID-19: Overview of Testing for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed April 25, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/testing-overview.html 12 WHO: Clinical Management of COVID-19: Interim Guidance. WHO website. Updated May 27, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1278777/retrieve 13 CDC: COVID-19: Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens for COVID-19. CDC website. Updated February 26, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html 14 CDC: Interim Guidance for Antigen Testing for SARS-CoV-2. CDC website. Updated December 16, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/antigen-tests-guidelines.html 15 Hanson KE et al: Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Diagnosis of COVID-19: Serologic Testing. IDSA website. Published August 18, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-serology/ 16 La Marca A et al: Testing for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): a systematic review and clinical guide to molecular and serological in-vitro diagnostic assays. Reprod Biomed Online. ePub, June 14, 2020 17 Babiker A et al: SARS-CoV-2 testing. Am J Clin Pathol. ePub, May 5, 2020 18 American College of Radiology: ACR Recommendations for the Use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography (CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection. ACR website. Updated March 22, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position- Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection 19 Hanson KE et al: Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Diagnosis of COVID-19. IDSA website. Published May 6, 2020. Updated December 23, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-diagnostics/ 20 WHO: Laboratory Testing for 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Suspected Human Cases: Interim guidance. WHO website. Updated March 19, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-331501 21 Phua J et al: Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. ePub, April 6, 2020 22 Mohammadi A et al: SARS-CoV-2 detection in different respiratory sites: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EBioMedicine. 102903, 2020 23 Gandhi RT et al: Mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 383(18):1757-66, 2020 24 Dinnes J et al: Rapid, point-of-care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 8:CD013705, 2020 25 Deeks JJ et al: Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6:CD013652, 2020 26 Wang D et al: Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel voronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. ePub, 2020 27 Yoon SH et al: Chest Radiographic and CT Findings of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Analysis of Nine Patients Treated in Korea. Korean J Radiol. 21(4):494-500, 2020 28 Shi H et al: Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 20(4):425-434, 2020 29 Kanne JP: Chest CT Findings in 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Infections from Wuhan, China: Key Points for the Radiologist. Radiology. 295(1):16- 17, 2020 30 Peng QY et al: Using echocardiography to guide the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Crit Care. 24(1):143, 2020 31 WHO: Infection Prevention and Control During Health Care When Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Infection Is Suspected: Interim Guidance. WHO website. Updated March 19, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-331495 32 CDC: COVID-19: Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Healthcare Personnel During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. CDC website. Updated February 23, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-controlrecommendations.html 33 FDA: FDA Approves First Treatment for COVID-19. FDA News Release. FDA website. Published October 22, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. 34 NIH: COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. NIH website. Updated April 21, 2021. Accessed April 25, 2021. https://covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ 35 Alhazzani W et al: Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines on the management of adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the ICU: first update. Crit Care Med. ePub, February 2021 36 Alhazzani W et al: Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Crit Care Med. ePub, March 27, 2020 37 Bhimraj A et al: Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Treatment and Management of Patients With COVID-19. IDSA website. Updated April 14, 2021. Accessed April 25, 2021. 38 Beigel JH et al: Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19--preliminary report. N Engl J Med. ePub, May 22, 2020 39 Beigel JH et al: Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19--preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 5;383(19):1813-1826. 40 RECOVERY Collaborative Group et al: Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19--preliminary report. N Engl J Med. ePub, July 17, 2020 41 Rinott E et al: Ibuprofen use and clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. ePub, June 12, 2020 42 American Society of Hematology: COVID-19 and VTE/Anticoagulation: Frequently Asked Questions. Version 9.0. ASH website. Updated February 25, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.hematology.org/covid-19/covid-19-and-vte-anticoagulation 43 Moores LK et al: Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of VTE in patients with COVID-19: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. ePub, June 2, 2020 44 Bikdeli B et al: COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-ofthe- art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 75(23):2950-73, 2020 45 Thachil J et al: ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 18(5):1023-1026, 2020 46 FDA: Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers: Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma for Treatment of COVID-19 in Hospitalized Patients. FDA website. Published August 23, 2020. Updated February 4, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/141478/download 47 Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center: Mortality Analyses. JHU website. Updated daily. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality 48 WHO: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. WHO website. Updated daily. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://covid19.who.int/

Cookies are used by this site. To decline or learn more, visit our cookie notice.

Copyright © 2025 Elsevier, its licensors, and contributors. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.