ThisiscontentfromElsevier'sDrugInformation

Lansoprazole

Learn more about Elsevier's Drug Information today! Get the drug data and decision support you need, including TRUE Daily Updates™ including every day including weekends and holidays.

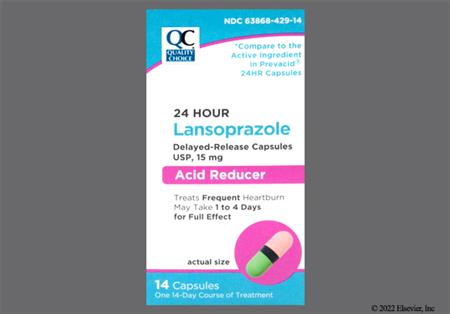

15 mg PO once daily for up to 14 days. Full relief may take 1 to 4 days. Reassess if heartburn returns after 14-day treatment regimen. For non-prescription use (self care) patient should not take for more than 14 days or more often than every 4 months unless directed by a physician.[60451]

15 mg PO once daily for up to 8 weeks.[40596] Per guidelines, may increase the dose (e.g. 30 mg/day and up to a maximum of 30 mg PO twice daily), in persons with partial response. Continue maintenance therapy at the lowest effective dose, including consideration of on-demand or intermittent therapy, in persons who continue to have symptoms after discontinuation.[55326] [68019]

15 mg PO once daily for up to 8 weeks.[40596] Doses of 30 mg/day have also been used.[71119] Alternatively, 0.7 to 3 mg/kg/day PO is suggested.[55232] Usual Max: 30 mg/day.[59478] [71138] [54890]

30 mg PO once daily for up to 12 weeks.[40596] Alternatively, 0.7 to 3 mg/kg/day PO is suggested.[55232] Initial doses of 1.4 to 1.5 mg/kg/day PO have been used, and doses of 1.5 mg/kg PO twice daily have been reported.[26957] [26958] [40596] [71119] Usual Max: 30 mg/day, although a few older studies have allowed higher doses for refractory patients.[59478] [71138] [53348] [53447] [54890]

15 mg PO once daily for up to 12 weeks.[40596] Alternatively, 0.7 to 3 mg/kg/day PO is suggested.[55232] Initial doses of 1.4 to 1.5 mg/kg/day PO have been used, and doses of 1.5 mg/kg PO twice daily have been reported.[26957] [26958] [40596] [71119] Usual Max: 30 mg/day, although a few older studies have allowed higher doses for refractory patients.[59478] [71138] [53348] [53447] [54890]

Limited data are available. Per guidelines, 2 mg/kg/day PO for 4 to 8 weeks.[59478] In infants 3 months and older, a dose of 15 mg PO once daily or 7.5 mg PO twice daily has been used.[53284] [71119] [71138] Doses of 1 to 2 mg/kg/day PO have been studied.[53284] [53435] Per the manufacturer, controlled study results do not support the use of lansoprazole to treat symptomatic GERD in infants. Lansoprazole 1 to 1.5 mg/kg/day PO for 4 weeks was not effective in symptomatic GERD in infants 10 weeks up to 1 year of age in a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, and adverse effects of heart valve thickening and bone changes at high doses have been reported in juvenile animal studies.[40596] [53284] In a retrospective analysis, the median lansoprazole dose was 1.74 mg/kg/day PO; the analysis did not evaluate clinical outcomes or safety.[33862] Nonpharmacologic therapy is recommended first for symptomatic GERD in otherwise healthy infants (1 to 11 months). Based on available studies, it is uncertain whether lansoprazole improves GERD signs and symptoms or leads to more side effects in infants compared to other treatments. Experts generally recommend PPIs or other acid suppression for infants with continued GERD alarm symptoms despite nonpharmacologic management or if they have erosive disease.[59478] [71119] [54890]

Limited data are available. Per guidelines, 2 mg/kg/day PO for 4 to 8 weeks.[59478] Doses of 1 or 2 mg/kg/day PO were reported to improve GERD symptoms in a small study.[53435] Per the manufacturer, controlled study results do not support the use of lansoprazole to treat symptomatic GERD in infants. Lansoprazole 0.2 to 0.3 mg/kg/day PO for 4 weeks was not effective in symptomatic GERD in infants 4 to 10 weeks of age in a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, and adverse effects of heart valve thickening and bone changes at high doses have been reported in juvenile animal studies.[40596] [53284] Nonpharmacologic therapy is recommended first for symptomatic GERD in otherwise healthy infants (1 to 11 months). Based on available studies, it is uncertain whether lansoprazole improves GERD signs and symptoms or leads to more side effects in infants compared to other treatments. Experts generally recommend PPIs or other acid suppression for infants with continued GERD alarm symptoms despite nonpharmacologic management or if they have erosive disease.[59478] [71119] [54890]

Limited data are available; safety and efficacy have not been established due to variability in efficacy reported and low numbers of neonates treated.[71119] Per the manufacturer, controlled study results in infants do not support the use of lansoprazole in treating symptomatic GERD in neonates or infants less than 1 year of age.[40596] A dose of 0.2 to 0.3 mg/kg/day PO for 4 weeks was used in patients 10 weeks and younger in 1 study; however, no difference in symptoms was noted between lansoprazole and placebo.[53284] Doses of 0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg/day PO, given in 1 or 2 divided doses, have been reported to reduce symptoms.[53435] In another study, 10 premature neonates (mean weight = 1.27 kg, mean postnatal age = 2 weeks) received lansoprazole 1.5 mg/kg/day PO divided into 2 doses. After 7 days of treatment, gastric pH was not above 2 in any patient.[59463]

30 mg PO once daily for up to 8 weeks. If healing is incomplete or recurs, consider an additional 8 weeks of treatment. Guidelines state dosage may be increased, up to 30 mg PO twice daily, in persons with partial response. For maintenance, 15 mg PO once daily. Periodically reassess the need for continued PPI therapy; controlled studies did not extend beyond 12 months.[40596] [55326] [68019]

30 mg PO once daily for up to 8 weeks.[40596] Pediatric trials for the healing of erosive esophagitis have shown consistently high rates of healing at PPI doses of 1 to 1.7 mg/kg/day PO. Based on expert opinion, PPIs are considered first-line treatment of reflux-related erosive esophagitis in children.[59478]

30 mg PO once daily for up to 12 weeks.[40596] Pediatric trials for the healing of erosive esophagitis have shown consistently high rates of healing at PPI doses of 1 to 1.7 mg/kg/day PO. Based on expert opinion, PPIs are considered first-line treatment of reflux-related erosive esophagitis in children.[59478]

15 mg PO once daily for up to 12 weeks.[40596] Pediatric trials for the healing of erosive esophagitis have shown consistently high rates of healing at PPI doses of 1 to 1.7 mg/kg/day PO. Based on expert opinion, PPIs are considered first-line treatment of reflux-related erosive esophagitis in children.[59478]

Limited data are available for the management of erosive GERD in infants.[71119] For infants 3 months and older, 15 mg PO once daily or 7.5 mg PO twice daily has been studied.[53437] [71138] Pediatric trials for the healing of erosive esophagitis have shown consistently high rates of healing at PPI doses of 1 to 1.7 mg/kg/day PO for up to 12 weeks, and guidelines list a lansoprazole dosage of up to 2 mg/kg/day PO for infants.[59478] Based on expert opinion, PPIs are considered first-line treatment of reflux-related erosive esophagitis in infants with GERD, as PPIs have exhibited better healing rates for erosive GERD in other patient populations vs. other agents.[59478]

60 mg PO once daily, initially. Adjust dose based on clinical response and tolerability. Max: 180 mg/day. Divide daily dosages more than 120 mg/day in 2 doses. Continue treatment for as long as clinically indicated; some individuals with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome have been treated continuously for more than 4 years.[40596]

Not recommended by guidelines.[63136] [69318] The FDA-approved dosage is 30 mg PO 3 times daily in combination with amoxicillin for 14 days.[40596]

30 or 60 mg PO twice daily in combination with clarithromycin and either amoxicillin or metronidazole for 14 days.[40596] [63136] [69318] The FDA-approved labeling suggests a 10 to 14 day treatment duration.[40596]

1.5 to 2.5 mg/kg/day PO divided twice daily (Max: 30 mg/dose) in combination with clarithromycin and either amoxicillin or metronidazole for 14 days.[63135]

30 mg PO twice daily in combination with clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and a nitroimidazole for 10 to 14 days.[63136] [69318]

1.5 to 2.5 mg/kg/day PO divided twice daily (Max: 30 mg/dose) in combination with clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and metronidazole for 14 days.[63135]

30 mg PO twice daily in combination with amoxicillin for 7 days, followed by 30 mg PO twice daily in combination with clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and a nitroimidazole for 7 days.[63136]

30 PO twice daily in combination with amoxicillin for 5 to 7 days, followed by 30 mg PO twice daily in combination with clarithromycin and a nitroimidazole for 5 to 7 days.[63136]

1.5 to 2.5 mg/kg/day PO divided twice daily (Max: 30 mg/dose) in combination with amoxicillin for 5 days, followed by 1.5 to 2.5 mg/kg/day PO divided twice daily (Max: 30 mg/dose) in combination with clarithromycin and metronidazole for 5 days.[63135]

30 mg PO twice daily in combination with levofloxacin and amoxicillin for 10 to 14 days.[63136] [69318] [69320]

30 mg PO twice daily in combination with levofloxacin and amoxicillin for 14 days.[63136] [69318] [69320]

30 or 60 mg PO twice daily in combination with amoxicillin for 5 to 7 days, followed by 30 or 60 mg PO twice daily in combination with levofloxacin and a nitroimidazole for 5 to 7 days.[63136]

60 mg PO once daily in combination with levofloxacin, nitazoxanide, and doxycycline for 7 to 10 days.[63136]

1.5 to 2.5 mg/kg/day PO divided twice daily (Max: 30 mg/dose) in combination with metronidazole and amoxicillin for 14 days.[63135]

30 mg PO twice daily in combination with rifabutin and amoxicillin for 10 days.[63136] [69318] [69320]

30 or 60 mg PO 3 or 4 times daily in combination with high-dose amoxicillin for 14 days.[63136] [69318] [69320]

30 mg PO twice daily in combination with bismuth subsalicylate, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 10 to 14 days.[63136] [69318]

1.5 to 2.5 mg/kg/day PO divided twice daily (Max: 30 mg/dose) in combination with bismuth subsalicylate, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 14 days.[63135]

1.5 to 2.5 mg/kg/day PO divided twice daily (Max: 30 mg/dose) in combination with bismuth subsalicylate, metronidazole, and amoxicillin for 14 days.[63135]

30 mg PO twice daily in combination with bismuth subsalicylate, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 14 days.[63136] [69318] [69320]

1.5 to 2.5 mg/kg/day PO divided twice daily (Max: 30 mg/dose) in combination with bismuth subsalicylate, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 14 days.[63135]

1.5 to 2.5 mg/kg/day PO divided twice daily (Max: 30 mg/dose) in combination with bismuth subsalicylate, metronidazole, and amoxicillin for 14 days.[63135]

30 mg PO twice daily in combination with bismuth subsalicylate plus 2 antibiotics for 10 to 14 days. Antibiotic combinations may include 2 of the following: amoxicillin, clarithromycin, levofloxacin, metronidazole, and tetracycline.[69318] [69319] [69320]

15 mg PO once daily in the morning at least 30 minutes before a meal, for up to 4 weeks. For maintenance of remission, 15 mg PO once daily in the morning at least 30 minutes before a meal may be continued; controlled studies did not extend beyond 12 months.[40596]

15 mg PO once daily in the morning at least 30 minutes before a meal, for up to 4 weeks. For maintenance of remission, 15 mg PO once daily in the morning at least 30 minutes before a meal may be continued; controlled studies did not extend beyond 12 months.[40596]

30 mg PO once daily in the morning at least 30 minutes before a meal, for up to 8 weeks.[40596]

30 mg PO once daily in the morning at least 30 minutes before a meal, for up to 8 weeks.[40596]

30 mg PO once daily for 8 weeks.[40596]

15 mg PO once daily. A higher dosage of 30 mg once daily has been evaluated for risk-reduction of NSAID-induced ulcers in a large multicenter trial; the larger dose yielded no additional benefit compared to the 15 mg dose.[40596]

30 mg lansoprazole once daily via nasogastric (NG) tube. May open capsule and pour one-quarter of the granules into a NG feeding syringe with the plunger removed. Slowly add water through the plunger end and push the water and granules through the tube by depressing the plunger. Repeat the process until all the granules are administered; flush the tube with 15 mL of water to administer any residual granules.[41385] The effect of daily NG lansoprazole on acid suppression was evaluated via continuous intragastric pH-metry for 3 days in 15 critically ill patients. After 2 days, the mean percentage of intragastric pH measurements of 4 or greater increased from 25% (+/- 13%) at baseline to 84% (+/- 14%) (p = 0.001).[41385]

30 mg lansoprazole disintegrating tablet once daily via nasogastric (NG) tube. Mix 30 mg in 10 mL of water, administer via nasogastric tube; flush tube with 10 mL of sterile water and clamp for 60 minutes.[41395] The effect of daily enteral lansoprazole was compared to IV lansoprazole in a study including 19 critically ill patients requiring stress ulcer prophylaxis. Enteral lansoprazole was found to maintain a gastric pH of 4 or greater for a duration longer than IV lansoprazole.[41395]

15 to 30 mg PO twice daily is suggested in the literature; treat for up to 8 weeks and continue until the time of the follow-up endoscopy and biopsy. Guidelines support the use of PPI therapy for EoE based on reports of reductions in histologic features of disease from 42% in observational studies.[65816] [65832]

30 mg/day PO for most indications; 90 mg/day PO is FDA-approved maximum for eradication of H. pylori; however, up to 120 mg/day PO is used off-label; up to 180 mg/day PO for Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

30 mg/day PO for most indications; 90 mg/day PO is FDA-approved maximum for eradication of H. pylori; however, up to 120 mg/day PO is used off-label; up to 180 mg/day PO for Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

30 mg/day PO for most indications; up to 60 mg/day PO has been used off-label for eradication of H. pylori.

12 years: 30 mg/day PO for most indications; up to 60 mg/day PO has been used off-label for eradication of H. pylori.

1 to 11 years weighing more than 30 kg: 30 mg/day PO for GERD or erosive esophagitis, up to 60 mg/day PO has been used off-label for refractory cases and for eradication of H. pylori.

1 to 11 years weighing 30 kg or less: 15 mg/day PO for GERD or erosive esophagitis, occasionally higher doses used for refractory cases; up to 2.5 mg/kg/day (Max: 60 mg/day) PO has been used off-label for eradication of H. pylori.

Safety and efficacy have not been established; doses up to 2 mg/kg/day PO have been used off-label for GERD.

Safety and efficacy have not been established; doses up to 1.5 mg/kg/day PO have been used off-label for GERD.

Mild to moderate hepatic impairment (Child Pugh Class A and B): No dosage adjustments are needed.

Severe hepatic impairment (Child Pugh Class C): 15 mg PO once daily.[40596]

Specific guidelines for dosage adjustments in renal impairment are not available; it appears that no dosage adjustments are needed.[40596]

Intermittent hemodialysis

Lansoprazole is not removed by hemodialysis.[40596]

† Off-label indication

Lansoprazole is an acid proton-pump inhibitor (PPI). It is used for the short-term treatment of duodenal or gastric ulcers, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and erosive esophagitis. It is also indicated to maintain healing of duodenal ulcer and esophagitis, for NSAID-induced ulcer treatment or prophylaxis, for long-term treatment of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (pathological hypersecretory condition), and for use in combination with antibiotics in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) to reduce the risk of duodenal ulcer recurrence.[63135][63136][40596] Nonprescription products are available for the relief of dyspepsia and heartburn.[60451] Clinicians should test for H. pylori infection in patients presenting with non-ulcer dyspepsia; patients found to be H. pylori positive should be started on combination eradication therapy.[33150] Eradication of H. pylori offers modest, but significant, symptom relief in non-ulcer dyspepsia and reduces the risk of developing peptic ulcer disease, atrophic gastritis, and gastric cancer.[33113] For populations with a low prevalence of H. pylori infection (less than 10%), starting a 2 to 4-week empiric trial of a PPI is an alternate approach.[33150] Per guidelines, no clear advantage has been demonstrated one PPI over another in the treatment of GERD. There are, however, wide variations in the acid-suppression potency with the following ranked from least to highest potency: pantoprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, esomeprazole, and rabeprazole. Therefore, a 1-time switch to a different PPI in a refractory patient may be useful. A key to optimizing effectiveness is tailoring dosage timing and considering twice daily dosing; traditional delayed-release PPIs should be administered 30 to 60 minutes before a meal for optimal response.[55326][68019] PPIs have been associated with an increased risk of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Lansoprazole was initially FDA approved in 1995.[40596]

For storage information, see specific product information within the How Supplied section.

Delayed-release capsules

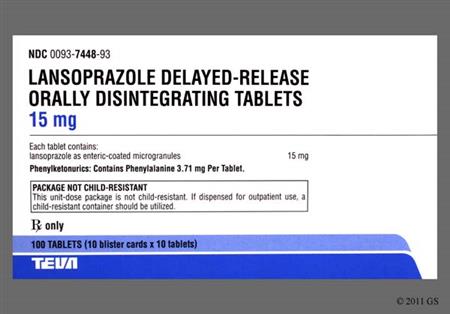

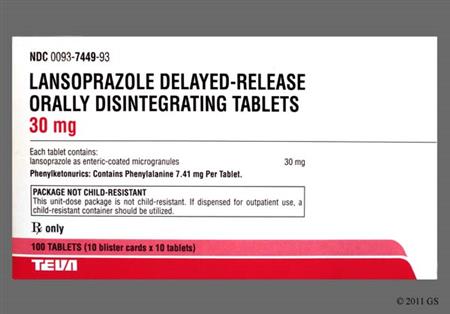

Delayed-release oral disintegrating tablets

Nasogastric (NG) Tube Administration

Capsules or oral disintegrating tablets can be administered via a NG tube.

Capsules: For administration into an NG tube size French 16 or greater. Open the capsule and mix the intact granules in 40 mL of apple juice. Using a catheter -tipped syringe, draw up the mixture and inject through the NG tube into the stomach. After administration, flush the NG tube with additional apple juice to clear the tube.[40596]

Disintegrating tablets: For administration into an NG tube size French 8 or greater. Dissolve in a catheter-tip syringe with water (4 mL for 15 mg tablet, 10 mL for 30 mg tablet). Shake gently for quick dispersal. After the tablet has dispersed, shake the catheter-tip syringe gently to keep the microgranules from settling, and immediately inject through the NG tube into the stomach. Administer within 15 minutes of mixing. Do not save the mixture for later use. Refill the catheter-tip syringe with approximately 5 mL of water, shake gently, and flush the tube.[40596]

Some products are not for tube administration. For example, Teva's lansoprazole delayed-release orally disintegrating tablet (ODT) has clogged and blocked oral syringes and feeding tubes, including both gastric and jejunostomy types, when the drug is administered as a suspension through these devices. If alternatives exist, the Teva lansoprazole delayed-release ODT product should not be administered through an oral syringe or feeding tube.[53386]

Extemporaneous preparation of oral suspension ('simplified lansoprazole suspension' or SLS)

NOTE: The extemporaneous preparation of lansoprazole suspension is not approved by the FDA.

The safety profile of lansoprazole is similar in adults, adolescents and children 1 to 17 years old. Adverse reactions reported during lansoprazole therapy (various dosages) during clinical trials were primarily gastrointestinal (GI) in nature. Constipation has been reported in controlled lansoprazole trials compared to placebo (1% vs 0.4%, respectively). In children 1 to 11 years old, the most frequent side effect was constipation (5%). Abdominal pain (2.1%), nausea (1.3%) and diarrhea (1.4% to 7.4%) were also reported at higher incidences than with placebo, and diarrhea appeared to be dose-related. Other GI related adverse events such as duodenitis, epigastric discomfort, esophageal disorder, hunger, hiatal hernia, and impaired gastric emptying were reported in a study where patients took either a COX-2 inhibitor or naproxen with lansoprazole. Additional GI adverse events occurring in less than 1% of patients receiving lansoprazole during clinical trials include: abnormal stools, anorexia, appetite stimulation, bezoar, dysgeusia, dyspepsia, dysphagia, enlarged abdomen, enteritis, eructation, esophageal stenosis, esophageal ulceration, esophagitis, flatulence, gastritis, gastroenteritis, gastrointestinal anomaly, gastrointestinal disorder, GI bleeding (positive fecal occult blood), glossitis, gum hemorrhage, halitosis, hematemesis, hypersalivation, increased gastrin levels, melena, mouth ulceration, gastrointestinal moniliasis, rectal disorder, stomatitis, stool discoloration, tenesmus, thirst, tongue disorder, ulcerative stomatitis, vomiting, and xerostomia. Liver toxicity, pancreatitis, and vomiting have been reported during postmarketing surveillance.[40596]

During clinical evaluation, headache was reported in more than 1% of patients taking lansoprazole. In patients being treated for H.pylori, headache was reported in 6% of patients receiving lansoprazole plus amoxicillin and clarithromycin triple therapy and in 7% of patients receiving lansoprazole and amoxicillin dual therapy. In pediatric patients, headache was reported in 3% of children aged 1 to 11 years and in 7% of patients aged 12 to 17 years. Other nervous system adverse reactions reported in less than 1% of all patients during clinical evaluation of lansoprazole include: abnormal dreams, agitation, amnesia, anxiety, apathy, confusion, dementia, depersonalization, depression, diplopia, dizziness, drowsiness, emotional lability, hallucinations, hemiplegia, hostility aggravated, hyperkinesis, hypertonia, hypoesthesia, insomnia, libido decrease, libido increase, migraine, nervousness, neurosis, paresthesias, seizures, sleep disorder, thinking abnormality, tremor, and vertigo. During postmarketing surveillance, speech disorder was also reported.[40596]

Cholelithiasis (less than 1%), hepatoxicity, hyperbilirubinemia, and elevated hepatic enzymes (increased AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, and GGTP) have been reported during lansoprazole therapy. In controlled clinical trials, 0.4% (4/978) placebo patients and 0.4% (11/2,677) lansoprazole patients had hepatic enzyme elevations more than 3 times the upper limit of the normal range at the end of the study, but without evidence of jaundice. Hepatotoxicity and pancreatitis have been reported postmarketing.[40596]

Hematological adverse reactions that have been reported in less than 1% of patients included anemia, hemolysis, and lymphadenopathy. During post-marketing surveillance, agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, hemolytic anemia, leukopenia, neutropenia, pancytopenia, thrombocytopenia, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) were also reported. In addition, the following laboratory parameter alterations were also reported as adverse events during clinical evaluation: abnormal RBC, increased globulins, increased/decreased/abnormal platelets, increased/decreased/abnormal WBC, eosinophilia, hemoglobin decreased, and hyperuricemia.[40596] Long-term (e.g., generally 2 to 3 years or more) treatment with acid-suppressing agents can lead to malabsorption of vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin).[40596] [56553] In a study of healthy volunteers, it was shown that omeprazole caused a significant reduction in cyanocobalamin absorption (vitamin B12 deficiency).[23614] One large case-controlled study compared patients with and without an incident diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency (n = 25,956 and 184,199, respectively). A correlation was demonstrated between vitamin B12 deficiency and gastric acid-suppression therapy. Patients receiving 2 years or more of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI)(OR, 1.65 [95% CI, 1.58 to 1.73]) or 2 years or more of a H2-receptor antagonist (OR, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.17 to 1.34]) were associated with having an increased risk for vitamin B12 deficiency. A dose-dependant relationship was evident, as daily doses greater than 1.5 PPI pills/day were more strongly associated with vitamin B12 deficiency (OR, 1.95 [95% CI, 1.77 to 2.15]) compared to daily doses less than 0.75 pills/day (OR, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.48 to 1.78]; p = 0.007 for interaction).[56553] The possibility of cyanocobalamin deficiency and pernicious anemia should be considered if clinical symptoms are observed. Neurological manifestations of pernicious anemia can occur in the absence of hematologic changes.

During clinical evaluation, rash was reported in less than 1% of patients receiving lansoprazole. Other dermatological reactions reported in less than 1% of lansoprazole-treated patients included: acne vulgaris, allergic reaction, alopecia, contact dermatitis, fixed eruption, hair disorder, maculopapular rash, nail disorder, pruritus, skin cancer/carcinoma, skin disorder, sweating (hyperhidrosis), urticaria, and xerosis (dry skin). Specific dermatological reactions reported during postmarketing surveillance include: anaphylactoid reactions, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis (some fatal), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Discontinue lansoprazole and consider further evaluation if patient develops signs or symptoms of severe cutaneous adverse reactions or other signs of hypersensitivity.[40596]

Colitis and ulcerative colitis have been reported among events occurring in less than 1% of lansoprazole-treated patients during clinical trials.[40596] In addition, the medical literature has suggested a link between lansoprazole and the onset of microscopic colitis. Reports and subsequent histological confirmation of both collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis, two distinct forms of microscopic colitis, have been observed in patients treated with lansoprazole. An idiosyncratic immune reaction to lansoprazole is suspected. Because small changes in the structures of PPIs may elicit different immunological responses, it is difficult to predict if this adverse effect can be expected with other PPIs. Clinicians should advise patients to report prolonged watery loose stools and lansoprazole discontinuation or substitution should be considered in these patients.[33152] [33191] In one case-control study, strong associations between current PPI use and both collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis were observed with all PPIs; the strongest association in this study was with the current use of lansoprazole.[71128]

Adverse events affecting the respiratory tract were reported in less than 1% of patients or subjects who received lansoprazole in clinical trials and include: asthma/bronchospasm, bronchitis, cough (increased), dyspnea, epistaxis, flu syndrome, hemoptysis, hiccups, laryngeal neoplasia, lung fibrosis, pharyngitis, pleural disorder, pneumonia, respiratory disorder (unspecified), upper respiratory inflammation/infections, rhinitis, sinusitis, and stridor.[40596] In addition, increasing evidence suggests a link between acid-suppression therapy and infection with pneumonia (community- and hospital-acquired). Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for this association. One such mechanism states that gastric pH serves as a barrier against pathogenic colonization of the gastrointestinal tract. An increase in gastric pH allows for bacterial and viral invasion which, in theory, can precipitate respiratory infections.[32661] Another proposed mechanism accounts for the role that gastric acid may have on stimulating the cough reflex that allows for the clearing of infectious agents from the respiratory tract. Finally, the fact that acid-suppressive therapy may impair white blood cell function, which in turn may lead to a depressed immune response to an infection, is listed among possible mechanisms.[35601] Regardless of the mechanism, the use of H2-blockers and/or PPIs has been associated with the development of pneumonia.[32661] [35601] Data from a large epidemiological trial, including 364,683 individuals who developed 5,551 first occurrences of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), suggest an increased risk of developing CAP among users of acid-suppressive therapy compared to those who stopped therapy. After adjusting for confounders, the adjusted relative risk (RR) for CAP among PPI users compared to those who stopped therapy was 1.89 (95% CI, 1.36 to 2.62). Likewise, users of H2-blockers had an adjusted RR of 1.63 (95% CI, 1.07 to 2.48) compared to those who stopped therapy.[32661] In a second large cohort trial, including 63,878 hospital admissions, acid-suppressive therapy was ordered in 52% (83% PPI and 23% H2-blocker, with some patients exposed to both) of new admissions. Hospital-acquired pneumonia occurred in 2,219 admissions (3.5%) with a higher incidence recorded among acid-suppressive therapy exposed patients compared to non-exposed patients. A subset analysis found a statistically significant association between PPI use (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1 to 1.4) and pneumonia. A non-significant association was found with H2-blockers (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.4); however, the lack of significance was attributed to the studies lack of power to detect significance for an OR of less than 1.3.[35601] Until more is known about the relationship between acid-suppression and pneumonia, clinicians are encouraged to carefully select patients before empirically initiating acid-suppressive therapy with H2-blockers or PPIs. A causal relationship between the use of lansoprazole and pneumonia has not been established.

The following genitourinary and reproductive system reactions have been reported in less than 1% of patients during lansoprazole clinical trials: abnormal menses (menstrual irregularity), breast enlargement, breast pain (mastalgia), breast tenderness, dysmenorrhea, dysuria, gynecomastia, impotence (erectile dysfunction), kidney calculus (nephrolithiasis), kidney pain, leukorrhea, menorrhagia, menstrual disorder, penis disorder, polyuria, testis disorder, urethral pain, increased urinary frequency, urinary retention, urinary tract infection, urinary urgency, urination impaired, and vaginitis. The following laboratory parameter alterations were also reported as adverse events during clinical evaluation of lansoprazole: albuminuria (proteinuria), crystal urine present (crystalluria), glycosuria, hematuria, and increased creatinine. In a study where patients took either a COX-2 inhibitor or lansoprazole and naproxen, renal impairment was reported. Urinary retention has been reported postmarketing. Acute tubulo-interstitial nephritis (AIN or TIN) has been observed in patients taking PPIs, including lansoprazole, and may occur at any point during PPI therapy. Patients may present with varying signs and symptoms from symptomatic hypersensitivity reactions to non-specific symptoms of decreased renal function (e.g., malaise, nausea, anorexia). In reported case series, some patients were diagnosed by biopsy and in the absence of extra-renal manifestations (e.g., fever, rash or arthralgia). Discontinue lansoprazole and evaluate patients with suspected acute AIN.[40596]

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and lupus-like symptoms have occurred in patients taking PPIs, including lansoprazole. Both exacerbation and new onset of existing autoimmune disease have been reported, with the majority of PPI-induced lupus erythematosus cases being CLE. Subacute CLE (SCLE) is the most common form of CLE reported in patients treated with PPIs, occurring within weeks to years after continuous drug therapy in patients ranging from infants to the elderly. Histological findings are usually observed without organ involvement. SLE is less commonly reported; PPI-associated SLE is generally milder than non-drug induced SLE. Onset of SLE typically occurs within days to years after initiating treatment, and occurs primarily in adults (young adults to geriatric). Most patients presented with rash; however, arthralgia and cytopenia were also reported. Do not administer PPIs for longer than medically indicated. If signs or symptoms consistent with CLE or SLE occur, discontinue the drug and refer the patient to the appropriate specialist for evaluation. Most patients improve with discontinuation of the PPI alone in 4 to 12 weeks; serological testing (ANA) may be positive and elevated serological test results may take longer to resolve than clinical manifestations.[40596]

During clinical evaluation of lansoprazole the following musculoskeletal adverse events were reported in less than 1% of the patient population: arthralgia, arthritis, back pain, bone disorder, joint disorder, leg muscle cramps, musculoskeletal pain, myalgia, myasthenia, neck pain, neck rigidity, ptosis, and synovitis. Myositis has been reported in postmarketing experience with lansoprazole.[40596] Several published observational studies suggest that proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy may be associated with an increased risk for osteoporosis-related bone fractures of the hip, wrist or spine. The risk of fracture was increased in patients who received high-dose (defined as multiple daily doses) and long-term PPI therapy (a year or longer).[40635] [40636] [40637] [40638] [40639] [40640] [40641] Use the lowest dose and shortest duration of PPI therapy appropriate to the condition being treated. In patients at risk for osteoporosis-related fractures, manage according to established treatment guidelines and ensure adequate vitamin D and calcium supplementation.[40596]

The following additional laboratory parameter alterations were reported as adverse events during clinical evaluation of lansoprazole: blood potassium increased (hyperkalemia) and increased/decreased electrolytes. Hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia have been reported during postmarketing lansoprazole use. Cases of hypomagnesemia have been reported in association with prolonged (3 months to more than 1 year) proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use. Hypomagnesemia may lead to hypocalcemia and/or hypokalemia and may exacerbate underlying hypocalcemia in patients at risk. Low serum magnesium may lead to serious adverse reactions such as muscle spasm (tetany), seizures, and irregular heartbeat (arrhythmias). Consider monitoring electrolyte concentrations and supplementing electrolytes when needed. Discontinuation of PPI therapy may be necessary.[43594] [40596]

Metabolic and nutritional adverse events reported with lansoprazole therapy in less than 1% of treated patients included: avitaminosis (vitamin deficiency, unspecified), gout, dehydration, hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, peripheral edema, weight gain or weight loss.[40596]

Endocrine system adverse effects reported in less than 1% of lansoprazole recipients in clinical studies included diabetes mellitus, goiter, and hypothyroidism.[40596]

Cardiovascular adverse events reported in less than 1% of patients during lansoprazole clinical trials included: angina, arrhythmia exacerbation, bradycardia, cardiospasm, cerebrovascular accident/cerebral infarction (stroke), hypertension, hypotension, myocardial infarction, palpitations, shock (circulatory failure), sinus tachycardia, syncope, and vasodilation. In addition, the following laboratory parameter alterations were also reported as adverse events during clinical evaluation of lansoprazole: hyperlipidemia, increased/decreased cholesterol, and increased LDH.[40596]

Adverse reactions reported with lansoprazole (less than 1%) for the body as a whole and not included elsewhere: abdomen enlarged, asthenia, back pain, candidiasis, carcinoma (new primary malignancy), chest pain (unspecified), chills, edema, fever, flu-like syndrome, malaise, pain, and pelvic pain. In a study where patients took either a COX-2 inhibitor or naproxen with lansoprazole, additional reactions included contusion, fatigue, hunger, hoarseness, and metaplasia.[40596]

Special senses adverse reactions reported in less than 1% of patients receiving lansoprazole included: abnormal vision (visual impairment), amblyopia, blepharitis, blurred vision, cataracts, conjunctivitis, deafness (hearing loss), dry eyes (xerophthalmia), ear/eye disorder, ocular pain, glaucoma (ocular hypertension), otitis media, parosmia, photophobia, retinal degeneration/disorder, tinnitus, and visual field defect.[40596]

C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) or pseudomembranous colitis has been reported with lansoprazole. PPI therapy, such as lansoprazole, may be associated with an increased risk of CDAD, especially in hospitalized patients. The use of gastric acid suppressive therapy, such as PPIs, may increase the risk of enteric infection or superinfection by encouraging the growth of gut microflora. If pseudomembranous colitis is suspected or confirmed, institute appropriate fluid and electrolyte management, protein supplementation, C. difficile-directed antibacterial therapy, and surgical evaluation as clinically appropriate.[40596] [48664] [53446] [55326]

Administration of lansoprazole may result in laboratory test interference, specifically serum chromogranin A (CgA) tests for neuroendocrine tumors, urine tests for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), secretin stimulation tests, and diagnostic tests for H. pylori. Gastric acid suppression may increase serum CgA. Increased CgA concentrations may cause false positive results in diagnostic investigations for neuroendocrine tumors. To prevent this interference, temporarily stop lansoprazole at least 14 days before assessing CgA concentrations and consider repeating the test if initial concentrations are high. If serial tests are performed, ensure the same commercial laboratory is used as reference ranges may vary. Reports have suggested use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may cause false positive urine screening tests for THC. If a PPI-induced false positive urine screen is suspected, confirm the positive results using an alternative testing method. Lansoprazole may cause a hyper-response in gastrin secretion to the secretin stimulation test, falsely suggesting gastrinoma. Health care providers are advised to temporarily stop lansoprazole at least 14 days prior to performing a secretin stimulation test to allow gastrin concentrations to return to baseline.[40596] PPIs are known to suppress H. pylori; thus, ingestion of a PPI within 2 weeks of performing diagnostic tests for H. pylori may lead to false negative results. At a minimum, instruct the patient to avoid the use of lansoprazole for at least 2 weeks prior to the test.[71839] [71841]

Studies suggest that long-term PPI therapy is associated with temporal gastric hypersecretion shortly following treatment discontinuation. A similar and well-established response has been noted after withdrawal of H2 blockers. Profound gastric acid suppression during PPI therapy leads to a drug-induced hypergastrinemia and subsequent rebound acid hypersecretion.[57393] In this hypersecretory state, enterochromaffin-like cell hypertrophy also results in a temporal increase in serum chromogranin A (CgA) levels.[40596] It is unclear, however, if this hypersecretory reflex results in clinically significant effects in patients on or attempting to discontinue PPI therapy. A clinically significant effect may lead to gastric acid-related symptoms upon PPI withdrawal and possible therapy dependence.[57394] Studies in healthy subjects (H. pylori negative) as well as GERD patients, present conflicting data regarding whether PPI therapy beyond 8-weeks is associated with rebound acid hypersecretion and associated dyspeptic symptoms shortly following PPI cessation.[57394] [57395] [57396] [57397] Until more consistent study results shed light on this possible effect, it is prudent to follow current treatment guidelines employing the lowest effective dose, for the shortest duration of time in symptomatic patients. For patients requiring maintenance therapy, consider on demand or intermittent PPI therapy, step down therapy to an H2 blocker, and regularly assess the need for continued gastric suppressive therapy.[55326]

Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use is associated with an increased risk of fundic gland gastric polyps. The risk for gastric polyps increases with long-term PPI use, especially beyond 1 year. Gastric polyps/fundic gland polyps have been reported during postmarketing surveillance with lansoprazole. Patients are usually asymptomatic, and the polyps are identified incidentally on endoscopy.[40596] Gastroduodenal carcinoids have been reported in patients with Zollinger-Ellison (ZE) syndrome receiving long-term lansoprazole; however, the ZE condition itself is known to be associated with such tumors. The overall risk of carcinoid tumors during PPI therapy is low based on cumulative safety experience; monitoring of serum gastrin levels during PPI therapy is generally not necessary.[26196] In one trial of patients (n = 25) with H2-receptor antagonist-resistant gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) treated with long-term (4 years or more) lansoprazole therapy, no cases of neoplasia or dysplasia were seen in biopsies.[24050] Use the shortest duration of PPI therapy appropriate to treat the specific condition. Symptomatic response to therapy with lansoprazole does not preclude the presence of gastric cancer or other malignancy. Consider additional follow-up and diagnostic testing in adults who have a suboptimal response or an early symptomatic relapse after completing treatment with a PPI. In older adult patients, also consider an endoscopy.[40596]

The coadministration of certain medications may lead to harm and require avoidance or therapy modification; review all drug interactions prior to concomitant use of other medications.

This medication is contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to it or any of its components.Lansoprazole is also contraindicated in individuals with a history of hypersensitivity to other substituted benzimidazoles [e.g., other proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)]. Before starting therapy with lansoprazole, carefully inquire about previous hypersensitivity reactions to PPIs.[40596]

People should consult their care team prior to nonprescription (OTC) use of lansoprazole if there is a history of the following: 1) heartburn for more than 3 months, 2) frequent wheezing - particularly with heartburn, 3) unexplained weight loss, 4) nausea or vomiting, or 5) stomach or abdominal pain. Individuals should not self-medicate with lansoprazole if they have trouble swallowing (dysphagia), vomiting with blood or bloody or black stools (symptoms of GI bleeding), heartburn with lightheadedness, sweating, or dizziness and/or chest pain or shoulder pain with shortness of breath; sweating; pain spreading to arms, neck, or shoulders; or lightheadedness (e.g., symptoms of coronary artery disease). These may be signs of a serious condition that requires medical evaluation and treatment.[60451]

In adults, symptomatic response to therapy with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) does not preclude the presence of gastric malignancy. Consider additional follow-up and diagnostic testing in adults who have a suboptimal response or an early symptomatic relapse after completing treatment with a PPI. In older adult patients, also consider an endoscopy.[40596]

Lansoprazole elimination is significantly prolonged in people with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh Class C) or hepatic failure and a dosage adjustment is recommended.[40596]

Use lansoprazole with caution in people with a pre-existing risk of hypocalcemia (e.g., hypoparathyroidism), hypokalemia, or hypomagnesemia; consider monitoring magnesium and calcium concentrations prior to initiating therapy and periodically while on treatment in at-risk patients. Supplement with magnesium and/or calcium as needed and consider discontinuing proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy if hypomagnesemia or hypocalcemia is refractory to treatment.[40596]

Use proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) with caution in people with an increased risk for osteoporosis. Several published observational studies suggest that PPI therapy may be associated with an increased risk for osteoporosis-related fractures of the hip, wrist, or spine. The risk of fracture was increased in patients who received high-dose, defined as multiple daily doses, and long-term PPI therapy (a year or longer). Use the lowest dose and shortest duration of PPI therapy appropriate to the condition being treated. People at risk for osteoporosis-related fractures should be managed according to established treatment guidelines.[40596]

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have been reported in people taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), including lansoprazole. These events have occurred as both new onset and an exacerbation of pre-existing autoimmune disease. Avoid use of PPIs for longer than medically indicated in these patients.[40596]

According to the Beers Criteria, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are considered potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) for use in geriatric adults due to the risk of Clostridium difficile infection, pneumonia, GI malignancies, and bone loss/fractures. Avoid scheduled use for more than 8 weeks except for high-risk adults (e.g., oral corticosteroids or chronic NSAID use), erosive esophagitis, Barrett's esophagitis, pathological hypersecretory condition, or a demonstrated need for maintenance treatment (e.g., due to failure of a drug discontinuation trial or inadequate response to H2-receptor blockers).[63923]

Lansoprazole oral disintegrating tablets contain aspartame, a source of phenylalanine. People with phenylketonuria should be aware of the amount of phenylalanine supplied in each tablet.[40596]

Published observational studies have not shown an association between lansoprazole use during pregnancy and adverse outcomes. However, these studies have methodological limitations that prevent definitive conclusions about drug-related risks. A prospective study by the European Network of Teratology Information Services compared 62 pregnant individuals taking a median of 30 mg of lansoprazole daily to 868 pregnant individuals not taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). There was no significant difference in major malformation rates (RR = 1.04; 95% CI 0.25 to 4.21). Additionally, a population-based retrospective cohort study in Denmark (1996 to 2008) found no significant increase in major birth defects following first-trimester exposure to lansoprazole in 794 live births. A meta-analysis of 1,530 individuals exposed to PPIs during the first trimester compared to 133,410 unexposed individuals, showing no significant increase in major malformations (OR = 1.12; 95% CI 0.86 to 1.45) or spontaneous abortions (OR = 1.29; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.97).[40596] [68893] Animal studies show no evidence of fetal harm. Rats and rabbits given up to 40 and 16 times, respectively, the recommended human dose of lansoprazole during organogenesis showed no adverse effects on fetal development. However, a rat pre- and postnatal toxicity study at 6.4 times the maximum recommended human dose found reduced femur weight, femur length, crown-rump length, and growth plate thickness (in males only) in offspring on postnatal day 21, related to decreased body weight gain; these effects were associated with reduction in body weight gain.[40596] Guidelines recommend a trial of lifestyle modifications as first-line therapy for heartburn and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) during pregnancy, followed by antacids if lifestyle adjustments are ineffective. For ongoing symptoms, histamine type 2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) can be used. PPIs should be reserved for pregnant patients who fail H2RA therapy.[68890] Self-medication with over-the-counter PPIs during pregnancy is not recommended. Pregnant patients should see their health care professional for proper diagnosis and treatment recommendations.[45899] [68890]

Lansoprazole is compatible with breast-feeding. Although there are no data on the presence of lansoprazole in human milk, transfer of the drug to milk and subsequent oral absorption in the breastfed child are expected to be minimal. Lansoprazole has been safely used in neonates and infants for clinical indications, and any exposure is unlikely to be harmful.[40596] [70364] [70365] Proton pump inhibitors may not be the preferred first-line agent. If heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms persist after delivery, antacids and sucralfate are also safe to use due to minimal presence in human milk. Histamine type 2-receptor antagonists like cimetidine and famotidine are present in human milk, but are considered compatible with breast-feeding and may be used if symptoms persist despite antacid use.[45899] [68890]

Lansoprazole belongs to the class of GI antisecretory agents, the substituted benzimidazoles, that suppress gastric acid secretion by inhibiting the (H+, K+)-ATPase enzyme system of parietal cells. An acidic environment in the parietal cell is required for conversion of gastric-acid pump inhibitors, such as lansoprazole, to the active sulfenamide metabolite. The active metabolite then inhibits the ATPase enzyme required for gastric-acid pump activation, thereby blocking the final step of acid output from the parietal cells. A significant increase in gastric pH and decrease in basal acid output occurs following oral administration of lansoprazole. In hypersecretory conditions, lansoprazole has a marked effect on gastric acid secretion, both basal- and pentagastrin-stimulated. Lansoprazole exerts an inhibitory effect on gastric acid for at least 24 hours, which allows a once-daily dosing schedule. Lansoprazole does not exhibit anticholinergic or histamine type-2 antagonist activity.[40596][53322] Lansoprazole induced increases in mucosal oxygenation or bicarbonate secretion may play a role in protecting the gastric mucosa from injury.[53348]

Acid suppression may enhance the effect of antimicrobials in eradicating Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori).[40596]

Lansoprazole has been shown to significantly decrease the basal acid output and significantly increase the mean gastric pH and the percent of time the gastric pH was greater than 3 and greater than 4. Lansoprazole also significantly reduced meal-stimulated gastric acid output and secretion volume, as well as pentagastrin-stimulated acid output. In patients with hypersecretion of acid, lansoprazole significantly reduced basal and pentagastrin-stimulated gastric acid secretion. Lansoprazole inhibited the normal increases in secretion volume, acidity and acid output induced by insulin. Increased gastric pH was seen within 1 to 2 hours with 30 mg orally of lansoprazole and 2 to 3 hours with 15 mg orally of lansoprazole. After discontinuation after multiple oral doses, the inhibition of gastric acid secretion as measured by intragastric pH gradually returned to normal over 2 to 4 days. There was no indication of rebound gastric acid.[40596]

In over 2,100 patients, median fasting serum gastrin levels increased 50% to 100% from baseline but remained within normal range after treatment with 15 to 60 mg of oral lansoprazole. These elevations reached a plateau within 2 months of therapy and returned to pretreatment levels within 4 weeks after discontinuation of therapy. Increased gastrin causes enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell hyperplasia and increased serum CgA levels. The increased CgA levels may cause false positive results in diagnostic investigations for neuroendocrine tumors. During lifetime exposure of rats with up to 150 mg/kg/day of lansoprazole dosed 7 days per week, marked hypergastrinemia was observed followed by ECL cell proliferation and formation of carcinoid tumors, especially in female rats. Gastric biopsy specimens from the body of the stomach from approximately 150 patients treated continuously with lansoprazole for at least 1 year did not show evidence of ECL cell effects similar to those seen in rat studies. Longer term data are needed to rule out the possibility of an increased risk of the development of gastric tumors in patients receiving long-term therapy with lansoprazole.[40596]

Lansoprazole did not significantly affect mucosal blood flow in the fundus of the stomach. Due to the normal physiologic effect caused by the inhibition of gastric acid secretion, a decrease of about 17% in blood flow in the antrum, pylorus, and duodenal bulb was seen. Lansoprazole significantly slowed the gastric emptying of digestible solids. Lansoprazole increased serum pepsinogen levels and decreased pepsin activity under basal conditions and in response to meal stimulation or insulin injection. As with other agents that elevate intragastric pH, increases in gastric pH were associated with increases in nitrate-reducing bacteria and elevation of nitrite concentration in gastric juice in patients with gastric ulcer. No significant increase in nitrosamine concentrations was observed.[40596]

Human studies for up to 1 year have not detected any clinically significant effects on the endocrine system. Hormones studied include testosterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), prolactin, cortisol, estradiol, insulin, aldosterone, parathormone, glucagon, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4), and somatotropic hormone (STH). Lansoprazole in oral doses of 15 to 60 mg for up to 1 year had no clinically significant effect on sexual function. In addition, lansoprazole 15 to 60 mg orally for 2 to 8 weeks had no clinically significant effect on thyroid function. In 24 month carcinogenicity studies in Sprague-Dawley rats with lansoprazole dosages up to 150 mg/kg/day, proliferative changes in the Leydig cells of the testes, including benign neoplasm, were increased compared to control rats.[40596]

No systemic effects of lansoprazole on the central nervous system, lymphoid, hematopoietic, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, or respiratory systems have been found in humans. Among 56 patients who had extensive baseline eye evaluations, no visual toxicity was observed after lansoprazole treatment (up to 180 mg/day) for up to 58 months. After lifetime lansoprazole exposure in rats, focal pancreatic atrophy, diffuse lymphoid hyperplasia in the thymus, and spontaneous retinal atrophy were seen.[40596]

Revision Date: 10/15/2025, 01:33:00 AMLansoprazole is administered orally. Lansoprazole is about 97% bound to plasma protein. Lansoprazole is believed to be transformed into 2 active inhibitors of acid secretion in the gastric parietal cells. Hepatic metabolism of lansoprazole is extensive and involves CYP3A4 and CYP2C19. The 2 identified hepatic metabolites of lansoprazole have little antisecretory activity. Plasma elimination half-life, which is less than 2 hours, is not related to gastric antisecretory effect, which lasts more than 24 hours. Elimination is believed to occur via biliary excretion. Almost no unchanged lansoprazole is detected in urine after single-dose administration. After administration of a single dose of radio-labeled lansoprazole, one-third of the administered radiation was excreted in urine and two-thirds in the feces.[40596]

Affected cytochrome P450 isoenzymes and drug transporters: CYP3A4, CYP2C19

Lansoprazole is a substrate of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 isoenzymes.[40596]

All lansoprazole oral dosage forms (capsules and disintegrating tablets) contain delayed-release, enteric-coated granules that release drug after they leave the stomach. Absorption of lansoprazole is rapid; mean peak plasma concentrations occur after about 1.7 hours. The absolute bioavailability is over 80%, which can be reduced by 50 to 70% if lansoprazole is given 30 minutes after food. The time to reach Cmax is also delayed by 3.5 to 3.7 hours when administered with food.[40596][53348] Antacids can also affect absorption and can cause a slight reduction in bioavailability.[53322]

Lansoprazole serum concentrations are increased in patients with hepatic disease. In patients with mild (Child-Pugh Class A) or moderate (Child-Pugh Class B) hepatic impairment, there was an approximate 3-fold increase in mean AUC compared to normal subjects. The corresponding mean plasma half-life was prolonged from 1.5 to 4 hours (Child-Pugh Class A) or 5 hours (Child-Pugh Class B). In patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, there was an approximated 6- and 5-fold increase in AUC, respectively, compared to health subjects.[40596]

Lansoprazole serum concentrations are not affected by renal dysfunction or hemodialysis. Pharmacokinetic parameters are not changed by the presence of renal impairment. Lansoprazole is not removed by hemodialysis.[40596]

Children

The pharmacokinetics of lansoprazole are similar for children, adolescents, and healthy adult subjects. The mean Cmax and AUC values are similar for 2 weight-adjusted dosage groups: 15 mg/day for those weighing 30 kg or less and 30 mg/day for those weighing more than 30 kg; pharmacokinetics are not affected by age or weight within these groups.[40596] The mean volume of distribution of lansoprazole in children is larger than reported in adults (0.6 to 0.9 L/kg vs. 0.39 to 0.46 L/kg).[53498] The mean elimination half-life ranges from 0.68 to 1.5 hours in children aged 1 to 11 years.[53348]

Neonates and Infants

The plasma exposure is higher and the elimination is lower after administration of lansoprazole to neonates and infants 10 weeks of age and younger compared to older pediatric patients and adults. In a pharmacokinetic study of neonates and infants with gastroesophageal reflux disease, neonates received doses of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day PO and infants received 1 to 2 mg/kg/day PO for 5 days. The half-life was increased (2 to 2.8 hours vs. 0.8 hours) and oral clearance was decreased (0.16 L/kg/hour vs. 0.61 to 0.71 L/kg/hour) in neonates, compared to infants. A post hoc examination of the data showed that infants 10 weeks and younger had Cmax and AUC values more than 2 and 5 times higher, respectively, than older infants. The mean half-life of lansoprazole was approximately 3 times greater in pediatric patients 10 weeks and younger compared to patients older than 10 weeks (2.3 hours vs. 0.8 hours).[53443] In another pharmacokinetic study of neonates, infants, and children with gastroesophageal reflux disease, doses of 0.5 and 1 mg/kg/day PO given to neonates and infants 10 weeks of age and younger resulted in higher mean weight-based normalized AUC values compared to adults who received a 30 mg dose. In infants older than 10 weeks of age, a dose of 1 mg/kg PO resulted in mean AUC values similar to that of adults who received a dose of 30 mg.[40596]

Lansoprazole serum concentrations are increased in older adults vs younger subjects. Geriatric adults have a reduced clearance and an increased elimination half-life (up to 2.9 hours) of lansoprazole; but drug accumulation was not observed during once-daily dosing.[40596]

Lansoprazole serum concentrations are not affected by gender. No clinically significant gender differences in clearance or AUC were determined.[40596]

Published observational studies have not shown an association between lansoprazole use during pregnancy and adverse outcomes. However, these studies have methodological limitations that prevent definitive conclusions about drug-related risks. A prospective study by the European Network of Teratology Information Services compared 62 pregnant individuals taking a median of 30 mg of lansoprazole daily to 868 pregnant individuals not taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). There was no significant difference in major malformation rates (RR = 1.04; 95% CI 0.25 to 4.21). Additionally, a population-based retrospective cohort study in Denmark (1996 to 2008) found no significant increase in major birth defects following first-trimester exposure to lansoprazole in 794 live births. A meta-analysis of 1,530 individuals exposed to PPIs during the first trimester compared to 133,410 unexposed individuals, showing no significant increase in major malformations (OR = 1.12; 95% CI 0.86 to 1.45) or spontaneous abortions (OR = 1.29; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.97).[40596] [68893] Animal studies show no evidence of fetal harm. Rats and rabbits given up to 40 and 16 times, respectively, the recommended human dose of lansoprazole during organogenesis showed no adverse effects on fetal development. However, a rat pre- and postnatal toxicity study at 6.4 times the maximum recommended human dose found reduced femur weight, femur length, crown-rump length, and growth plate thickness (in males only) in offspring on postnatal day 21, related to decreased body weight gain; these effects were associated with reduction in body weight gain.[40596] Guidelines recommend a trial of lifestyle modifications as first-line therapy for heartburn and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) during pregnancy, followed by antacids if lifestyle adjustments are ineffective. For ongoing symptoms, histamine type 2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) can be used. PPIs should be reserved for pregnant patients who fail H2RA therapy.[68890] Self-medication with over-the-counter PPIs during pregnancy is not recommended. Pregnant patients should see their health care professional for proper diagnosis and treatment recommendations.[45899] [68890]

Lansoprazole is compatible with breast-feeding. Although there are no data on the presence of lansoprazole in human milk, transfer of the drug to milk and subsequent oral absorption in the breastfed child are expected to be minimal. Lansoprazole has been safely used in neonates and infants for clinical indications, and any exposure is unlikely to be harmful.[40596] [70364] [70365] Proton pump inhibitors may not be the preferred first-line agent. If heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms persist after delivery, antacids and sucralfate are also safe to use due to minimal presence in human milk. Histamine type 2-receptor antagonists like cimetidine and famotidine are present in human milk, but are considered compatible with breast-feeding and may be used if symptoms persist despite antacid use.[45899] [68890]

Cookies are used by this site. To decline or learn more, visit our cookie notice.

Copyright © 2025 Elsevier, its licensors, and contributors. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.